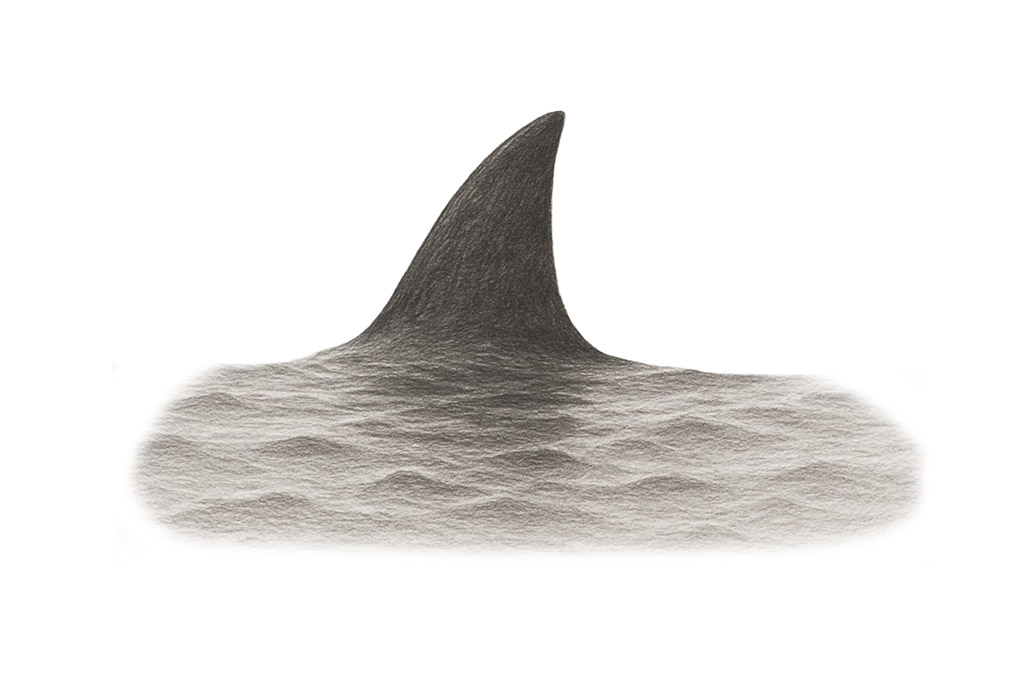

Fifty years ago, Jaws exploded onto cinema screens. Alongside terrifying beachgoers, it changed how movies were made, marketed, and monetised. But beyond the unconvincing fake shark and that sinister two-note score, Jaws also holds unexpected lessons about authority, trust and credibility relevant to anyone interested in human behaviour.

Believe it or not, there are at least nine types of authority: Expert, Experiential, Charismatic, Common Sense, Institutional, Moral, Cultural, Peer and Symbolic. Jaws’ potency lies not in the creature beneath the water, but in the struggle for authority between the three men who set sail to face it.

Brody represents Common Sense Authority, grounded in pragmatism and public duty. He voices the townspeople’s fears with his reasonable view that when something is eating people, it’s probably a good idea to stop it. His authority comes from being relatable and embodying civic responsibility. We trust Brody because his concerns match our intuitive sense of risk – he voices what ‘any reasonable person’ might think facing danger.

Hooper is the intellectual, armed with expensive technology, academic credentials and scientific knowledge. His authority derives from the heuristic that if someone’s studied something long enough and has enough degree certificates, they must know what they’re talking about. Referring to the troublesome fish by its Latin name, he represents Expert Authority – the analytical response to danger and conviction that technical knowledge leads to the best course of action.

Quint is the hardened veteran, seasoned by trauma and decades of hands-on shark encounters. Unlike Hooper, who learned from books, Quint learned the hard way: being in water with them when they were hungry. He represents Experiential Authority. Quint’s most memorable contribution comes through his USS Indianapolis speech – that haunting monologue about surviving one of the war’s most horrific shark attacks.

Before that sobering moment, we witness perhaps the most honest depiction of male authority-establishment ever filmed. It starts with Hooper showing off a shark bite scar – an academic’s attempt to prove his street credentials. Brody, not to be outdone, starts lifting his shirt but wisely realises his appendectomy scar probably won’t impress this company.

Then it’s Quint’s turn. What follows is a masterclass in how experiential authority establishes itself. He doesn’t just show scars, he narrates them, each a chapter in his survival story. The wrestling injury, the thresher shark scar, themysterious removed tattoo – each serving as credentials no university could confer. It culminates with his unmatchable tale of experiential authority – the USS Indianapolis story, so harrowing you can hardly believe it happened outside a novel.

This pivotal scene reveals the primitive nature of authority struggles. Three grown men drunkenly trying to prove worthiness, their scars as résumés. Does Quint win? We’re left to decide – exactly at this point, our toothy friend returns, rudely interrupting proceedings.

What Jaws teaches us about authority:

1. Authority is contextual, not absolute

We don’t just trust one kind of authority. We weigh different signals depending on situation. Sometimes we trust the expert with fancy equipment; sometimes the grizzled veteran with scars; sometimes the ordinary person with common sense. Authority bias is fluid and shifts under stress.

2. Diverse forms of authority can be both strength and weakness

Authority isn’t zero-sum. We need different types – voice of reason, weight of knowledge, wisdom of experience – despite the inevitable friction this creates. Jaws doesn’t declare an authority contest winner. Each type proves both essential and insufficient, trustworthy and fallible. Brody’s common sense says, ‘Close the beach’; Hooper’s expertise identifies the shark; Quint’s experience knows how to hunt it. Collectively, their diverse perspectives give them a fighting chance.

3. Narratives expose our trust biases

Watch Jaws with others, and you’ll notice people gravitate toward one of the three shark hunters, revealing their own trust predispositions. And allegiances shift at different film moments. Watching Jaws is a mirror to our own psychological biases and inconsistencies.

Fifty years on, the shark may look fake, but authority lessons remain relevant – perhaps more so nowadays where everyone’s metaphorically lifting their shirts online to prove their credentials. Deciding who to trust, and when, is a key life skill. It’s helpful to recognise different kinds of authority at play in any situation – and our own biases in how we respond to them.

Sarah