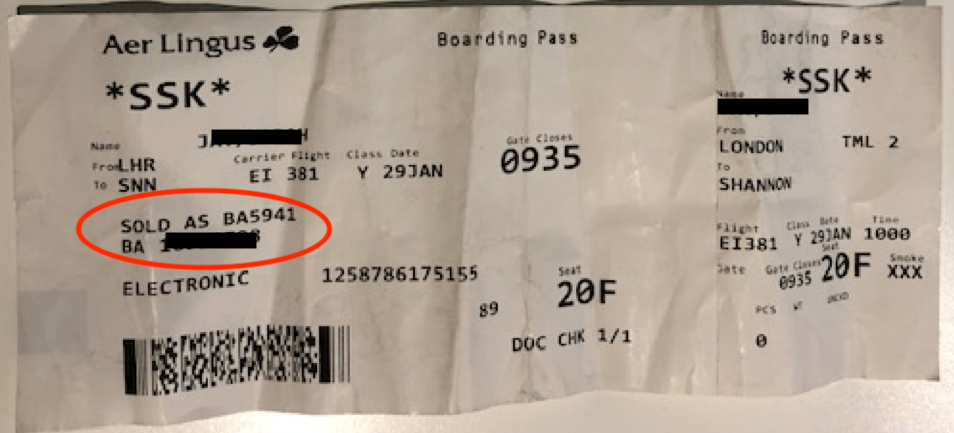

Have you ever booked a flight with an airline, only to discover at the airport that, in fact, you’re travelling with an entirely different carrier? Earlier this year one of our team was flying to Ireland with BA. Or so we thought. On arrival, the boarding card revealed that the carrier would be Aer Lingus, starkly confirmed with the words ‘Sold as BA’.

Code sharing is common practice in the airline industry, to the point where people don’t really talk about it. But when you think about it, it’s actually quite startling practice from a customer perspective. Consider what the equivalent would look like in another category –perhaps placing an order with Sainsbury’s, only to have a Tesco van pull up outside, the delivery guy reassuring you that, it’s OK, because the order was only ‘sold as Sainsbury’s’.

This got us thinking about the gap between businesses and their brands. Of course, in principle there shouldn’t be a gap at all. In an ideal world, brand and business would be in harmony, and the business wouldn’t have any internal conversations that they wouldn’t want their customers to hear, because it would operate perfectly in line with its carefully crafted brand values.

When a business doesn’t behave in line with its brand, cracks appear and the brand is exposed as a mask. As customers, we’re not privy to the details, but we sense that they’re up to something. We become alert to jargon, small print and weasel words, all of which point to the business doing something it’s not proud of. Consider the opacity of banking brands running up to the 2008 financial crisis, the VW emissions scandal or Facebook and its murky Cambridge Analytica associations.

Code sharing is an example of the needs of the business being so paramount, that they create decision-making that the brand would never do. The business wins out over the brand – a glimpse of corporate reality under the hood. Suddenly the brand feels superficial, as though we’ve been duped. The gap between brand and business practice is brought sharply to the fore.

We experience this sense of dissonance across a wide variety of categories, for example when a brand’s CSR claims don’t quite tally with its actual commitment to a cause, or when a brand’s sales tactics feel out of sync with what it stands for. Recently Ted Baker introduced a series of Booking.com-style behavioural nudges onto its website (‘8 other people are eyeing this up! 6 other people bought this today!) which made browsing considerably less pleasant and jarred with its premium image.

So what can we learn from all of this?

- As a measure of your brand/business coherence, ask yourself, ‘Is this business conversation one that the brand would make?’ or, ‘What’s in it for the customer?’ It’s a good way of raising a red flag during the decision-making process. If the answer is no or nothing, then perhaps you need to reconsider.

- If your business is forced to act out of character with its brand, don’t expect people not to notice or care. Code sharing may have become a modern commercial reality, but airlines can and should be more upfront about the practice from the moment of purchase. Can the move be re-framed more positively e.g. by drawing attention to the increased flexibility of partnering with a trusted alliance or perhaps cheaper options. Sleight of hand undermines trust.

- People pay for brands precisely because they are buying into an intangible benefit over and above the intrinsic value of the product. Burberry demonstrated a strong grasp of this when they controversially burnt leftover merchandise to avoid cheap re-sale and protect their brand exclusivity.

- Just because something is technically feasible doesn’t mean you should implement it. Ted Baker recently retracted their BE nudge tactics, presumably in response to customer complaints. Happy, relaxed online shopping with them has since resumed.

Mind the gap between your brand and your business.